Brindabella Chronicles Introduction

Dai Davies, 210308

Brindabella Chronicles is a series of three noves set at the turn of the twenty-third century and in two locations. The first is a small community in the Brindabella Valley of south-eastern New South Wales. It's a Janeite community – one of a few "retro" or "neo-" communities of the time which, with minimal use of modern technologies recreates the world of Jane Austen. The second location is Arkadel, one of the most advanced societies of the day based in a floating city in the centre of the Pacific Ocean. It's a "swarm hive" society where residents gear their lives, or prepare their Personal Archive (PA), for galactic exploration. It's from Arkadel that our main character sets out on her voyage of exploration which leads her to Brindabella.

Book 1

Being Human is an exploration of who we are as individuals – what makes us tick at a biological level through to mind and consciousness. Although the activity of our brain is highly complex, the essence of its basic operation can be readily appreciated if we look at the whole brain rather than just neurons. This view was introduced by Renato Nobili in the 1980s when he recognised the role played by the dominant cell-type in the brain – glial cells, which he characterised as forming a holographic memory system. For me, taking a systems engineering perspective, just neurons acting alone didn't make sense. Including this glial function provided what I knew to be missing.

With an optical hologram a two dimensional photograph is capable of presenting a three dimensional image. While glia exist in a three dimensional mass, their interconnections create a structure which can represent far more dimensions. Some insight into this may be seen briefly in transcendental experiences, when time is folded into the three spatial dimensions to give an impression of infinite time. This is not a very practical perspective, and most people who experience it in a waking state are pleased to return to their normal one. None-the-less, a single such experience can be life-changing.

Fundamentally, the brain is a massively parallel pattern recognition system. Looking at it from this perspective can give valuable insights into our behaviour. In particular, it provides a basis for understanding our unconscious mind: how it deals with the almost infinite complexity of our sensory experience and our reflections on them, then feeds our consciousness with a distillation of what is of greatest significance. This feed is serial, and simple enough to be represented in language or visual imagery.

This has long been recognised, with reflective meditation techniques developed in the distant past to help us understand ourselves. Recent attempts at developing artificial intelligence, which attempts to mimic the operation of our minds, has increased awareness of the enormous complexity involved. That our brains achieve what they do is truely awe-inspiring.

Recently I've been exploring what seems to be a natural and inevitable parallel between how our brains function and how we structure our corporate and social institutions. Not a new idea, it has our conscious mind as the board of directors acting on information collected and distilled by relevance in the whole institution – the "body corporate".

This view can help us deal with the reality of our multiple personalities. We are not just one. Putting aside our genetic inheritance, even before we have what we might consider a "self" we are observing and coming to some understanding of our parents' appearance and behaviour. Only as we start to understand and interact with them and others does a "self" start to develop. To engage in meaningful interaction with other individuals we must establish an understanding, or model, of each of them. Failure to do this leads to some degree of autism.

In this book we look at an approach to dealing with a particular problem we are currtently facing, one which threatens to challenge our human nature: how to live a human existence while still harnessing the potential benefits of arificial intelligence (AI). Currently we are well down the path of centralised AI – a path that leads inevitably to totalitarianism – a slave society. The natural solution to this is to devolve AI down to a personal level with AI used to extend our individual abilities rather than control us from above.

The particular solution discussed here is the Personal Archive, a life-long archive of an individual's experience with AI abilities tuned to matching how we are interpreting and reacting to these experiences. A central theme of this book, and the primary concern of our main character, is how accurately a PA might replicate the character of its owner and live on in the PA afterlife as an active and creative agent – albeit under the supervision of a living human.

Book 2

Children at the Gates of Dawn looks at the role of children's stories in introducing us to the complexities and difficulties of life as a human who is capable of asking the questions "Why are we here?" and when life gets hard "Why do we bother?" and "Where are we going? Is there a future worth striving for?". In the past, for most people, basic day-to-day physical survival has held these questions at bay.

Trying to predict even the near future may be a futile task, and experience tells us that we are likely to embarrassingly wrong, but it may be possible to steer away from obvious dangers. AI poses such an existential threat and challenge for the near future.

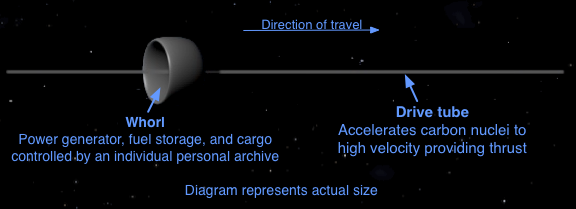

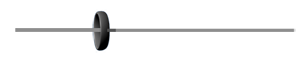

Beyond that, we look at how an authentic PA might lead to the exploration, and even settlement, of our galactic neighbourhood by piloting tiny space craft – spindles. Millions of these are assembling around Neptune ready to set off in swarms into our galactic neighbourhood.

A spindle

This is the primary motivation of our central character and her fellow Arkadelians. She is picking up the challenge of her great grandmother who was the first to propose that establishing colonies of flesh-and-bone humans might some day be possible.

Book 3

The Evolution of Gods looks at the evolution of human societies and the role of religions in passing ideas and practices that have worked down through generations and millennia, as evinced by the survival of societies that have followed these practices rather than alternatives which have lead to social decay and ultimate demise.

A clearer understanding of our unconscious mind sheds light on its relationship with a society's collective unconscious. This has evolved down through the generations since the first days of our human existence as a social animal – passed through common habits, and mythology which codifies and reifies those habits and views that have survived.

The most complex set of patterns or models that human minds have developed are those that represent our self-image and how we view others. It's not surprising, then, that societies have repeatedly presented the wisdom passed down from the past in the form of an anthropomorphic god.

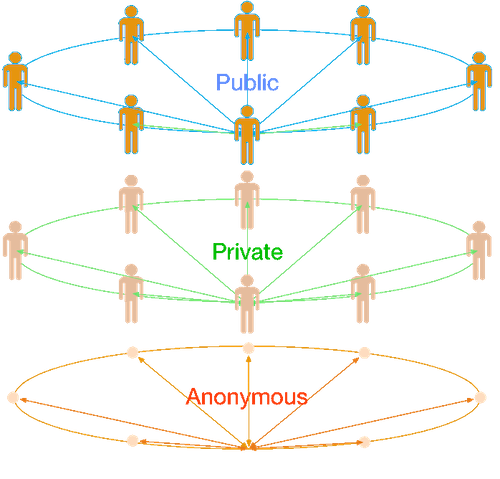

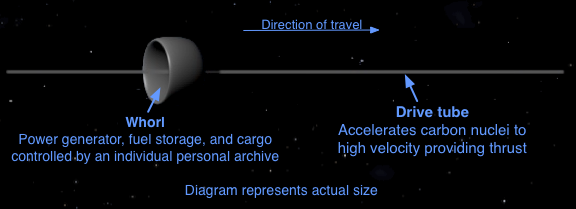

The question "Does Arkadel have a God?" is posed. The tentative answer is that the network of anonymous PA communications which has evolved in Arkadel has established a form of collective unconscious. Within this, general principles governing the dynamics of the Arkadel community are evolving along with some constraints on individual behaviour that keep conflict within acceptable bounds.

PA communications levels

The patterns our brain detects and elaborates are not generally verbal logic. This ability is best viewed as an epiphenomenon – a product of the relatively recent human expansion of language. Logic depends on the elaboration and verification of propositions or presumptions. These not only have to be correct, but all-inclusive. Outside the bounds of mathematics and formal logic this is rarely, if ever, achieved.

The idea that The Enlightenment ushered in an Age of Reason is at best relative, but largely illusory. This book suggests that by the twenty-third century a Second Enlightenment is approaching, ushering in an Age of Wisdom – an age when the deductive truth of observation is augmented by a consequential truth of those beliefs and actions which lead to success.

What this book doesn't address explicitly is a social phenomenon which has risen to prominence since I wrote it. It is the problem of "identity". Specifically, do we see others as individuals who we need to assess as such, or can we just deal with the categorisations that our minds readily provide, and become re-enforced by our innate need to belong? The simple answer is that we need to be capable of both.

A more useful answer is that we need to look carefully at how the role of the family and how we introduce children to society has changed. We need to ask "by whom and why?". The nature of totalitarianism is addressed in this book, but the questions also lead us back to Book 2 as a pointer to a response.

A spindle

A spindle

PA communications levels

PA communications levels